Colds and the flu

Highlights

Overview

- Upper respiratory tract infections affect the air passages in the nose, ears, and throat.

- Organisms that cause these upper respiratory tract infections are generally spread by direct contact (such as hand-to-mouth) with germs or by someone coughing or sneezing.

- The common cold is the most common upper respiratory tract infection.

Flu Vaccine

The CDC recommends that everyone over the age of 6 months receive the flu vaccine every year. The only exceptions are for those allergic to the vaccine. Two types of flu vaccine are available: a killed vaccine that comes in 3 injectable forms, and a live vaccine given as a nasal spray.

There are 3 types of influenza injectable vaccines:

- The regular killed vaccine is licensed for use in everyone 6 months and older.

- The intradermal injection uses a much smaller needle and dose, and is injected into the skin instead of the muscle.

- The high-dose injection is for people 65 and older. This vaccine delivers a much higher dose of the antigens.

H1N1 Flu

- H1N1 (the “swine flu”) is still circulating as one of the flu strains in the 2011- 2012flu season.

- The seasonal flu vaccine given during the 2011- 2012flu season also provides protection against H1N1.

Cold and Flu Treatments

- Antibiotics are very often inappropriately prescribed for non-strep sore throats. Studies indicate that fewer than half of adults and far fewer of the children with even strong signs and symptoms for strep throat actually have strep infections.

- A nasal wash can be helpful for removing mucus from the nose.

- Dozens of remedies are available that combine ingredients aimed at more than one cold or flu symptom. In general, they do no harm, but they have problems. Some ingredients may produce side effects without even helping a cold. In some cases, the ingredients conflict (such as a cough expectorant and a cough suppressant). In other cases, a patient may wish to increase the dosage to improve one symptom, which serves to increase other ingredients that do no good and, in higher doses, may cause side effects.

Introduction

Upper respiratory tract infections affect the air passages in the nose, ears, and throat.

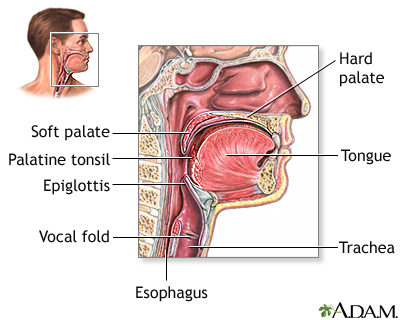

Structures of the throat include the esophagus, trachea, epiglottis, and tonsils.

The infections can be caused by viruses, bacteria, or other microscopic organisms. In most cases, these infections lead to colds or mild influenza (flu) and are temporary and harmless. In rare cases, flu can be severe, or the infections may turn into pneumonia.

Organisms that cause these upper respiratory tract infections are generally spread by:

- Direct contact (such as hand-to-mouth)

- Coughing or sneezing

The Common Cold

The common cold (medically known as infectious nasopharyngitis) is the most common upper respiratory tract infection. More than 200 different viruses can cause colds. The most common cause is the rhinovirus, which is responsible for about half of all colds. Symptoms usually develop 1 - 3 days after being exposed to the virus.

A cold usually progresses in the following manner:

- It nearly always starts rapidly with throat irritation and stuffiness in the nose.

- Within hours, full-blown cold symptoms usually develop, which can include sneezing, mild sore throat, fever, minor headaches, muscle aches, and coughing.

- Fever is low-grade or absent. In small children, however, fever may be as high as 103 °F for 1 or 2 days. The fever should go down after that time, and be back to normal by the 5th day.

- Nasal discharge is usually clear and runny the first 1 - 3 days. It then thickens and becomes yellow to greenish.

- The sore throat is usually mild and lasts only about a day. A runny nose usually lasts 2 - 7 days, although coughing and nasal discharge can persist for more than 2 weeks.

The adenovirus family also causes upper respiratory infections (it is one of the many viruses that cause the common cold). It also causes pneumonia, conjunctivitis, and several other diseases. A newer strain of adenovirus has resulted in several deaths.

Influenza ("The Flu")

Every year, influenza strikes millions of people worldwide. Influenza epidemics are most serious when they involve a new strain, against which most people around the world are not immune. Such global epidemics (pandemics) can rapidly infect more than one fourth of the world's population. For example, the Spanish flu in 1918 and 1919 killed an estimated 20 million people in the U.S. and Europe and 17 million people in India. With modern society's dependence on air travel, an influenza pandemic could potentially inflict catastrophic damage on human lives, and disrupt the global economy.

More recently, the new H1N1 ("Swine Flu") that emerged in Mexico in the spring of 2009 quickly became a pandemic, though it is far less severe or deadly than the Spanish flu of 1918. As of February 24 2010, the World Health Organization estimated the total deaths from the H1N1 pandemic at over 16,000 people. It is likely the actual total is somewhat larger, because not all victims are tested for H1N1 influenza. The H1N1 pandemic was declared over by the World Health Organization in August 2010. This particular influenza strain became one of the seasonal influenza viruses circulating world-wide during the 2010 -2011, and to a lesser extent during the 2011 - 2012 flu season.

Symptoms of influenza. Patients usually feel sick 1 - 2 days after exposure to the influenza (flu) virus. The flu usually involves:

- Abrupt onset of severe symptoms, which include headache, muscle aches, fatigue, and high fever (up to 104 °F).

- Cough (which is usually dry but is often severe) and sometimes a runny nose and sore throat.

- Children may experience vomiting, diarrhea, and ear infections, as well as other flu symptoms.

- The symptoms usually resolve in 4 - 5 days, although some people can experience coughing and feelings of illness for more than 2 weeks. In some cases, flu can become more severe or make other conditions worse.

Transmitting the Virus. The flu virus is spread primarily when a person with the flu coughs or sneezes near someone else. Adults with flu typically spread it to someone else from 1 day before symptoms start to about 5 days after symptoms develop. Children can spread the infection for more than 10 days after symptoms begin, and young children can transmit the virus 6 days or even earlier before the onset of symptoms. People with severely compromised immune systems can transmit the virus for weeks or months.

Flu Strains. A virus is a cluster of genes wrapped in a protein membrane, which is coated with a fatty substance that contains molecules called glycoproteins. Strains of the flu are identified according to the number of membranes and type of glycoproteins present.

The two major flu strains are referred to as A and B:

- Influenza A is the most widespread and can infect animals and humans. Influenza A is the cause of the major pandemics of influenza that have occurred so far. It is usually further categorized by two subtypes based on two substances that occur on the surface of the viruses: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N).

- Influenza B infects only humans. It is less common than type A, but is often associated with specific outbreaks, such as in nursing homes.

The vast majority of flu cases are type A. Influenza A usually causes more severe disease than type B. There is some concern, however, that since influenza B has been less common in the past few years, some people, particularly small children, may have fewer antibodies to it and so may be at higher risk for severe infection.

H1N1 (Swine) Influenza

In April 2009, an outbreak of a new influenza virus, also known as swine influenza, began in Mexico and spread to the United States and other countries. Swine influenza is flu infection found in pigs. The virus that causes this infection in pigs can change (mutate) to infect humans. The disease is of concern to humans, who have no immunity against it. By June 2009, the World Health Organization had declared a worldwide swine flu pandemic, but by August 2010, the pandemic had ended.

The current strain of swine flu virus has been identified as H1N1. The virus is contagious and can spread from human to human. Symptoms in humans are similar to classic flu symptoms, which might include fever, cough, sore throat, headache, chills, fatigue, dizziness, lack of energy, diarrhea, and vomiting.

A safe and effective vaccine is now widely available, and was incorporated into the annual flu vaccine for the 2011 - 2012 season.

Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)

The influenza virus mutates (changes) rapidly as it moves from species to species. While most avian influenza (bird flu) virus strains are relatively harmless, a few develop into "highly pathogenic avian influenza," which can be very deadly for domesticated poultry. As recent events have shown, these strains can also be deadly to humans. People can become infected by these bird flu strains through contact with contaminated chickens and other birds. The medical community is concerned about the H5N1 bird flu virus, which has infected and killed people in several countries.

Since 1997, the H5N1 virus has triggered deadly outbreaks in poultry across Southeast Asia. As of December 15, 2011, 573 people had been infected with the bird flu in 15 countries. Of these people, 336 have died, according to the World Health Organization. No cases have been reported in the United States.

So far, the virus has spread only from birds to humans. The virus does not seem to be easily spread from person to person. However, scientists and public health officials are monitoring the spread of H5N1 and working to contain it. Efforts include slaughtering infected birds, developing new vaccines, and stockpiling antiviral drugs such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu). Many poor nations have limited resources and already contend with other serious health problems, including HIV-AIDS. If H5N1 does mutate and spread, the consequences could be especially severe for these countries.

In April 2007, the FDA approved a vaccine to protect humans from avian influenza. Currently this vaccine is not being used for routine immunization. However, if the avian flu develops the ability to spread fairly easily from human to human, this vaccine may be made available. A new avian influenza vaccine is currently in clinical trials and is showing

promising results.

Diagnosis

Differentiating between a cold and flu may be difficult. Cold symptoms are nearly always less severe than those of the flu.

Comparing Colds and Flus | ||

| Symptoms | Cold | Flu |

Fever | None or low grade | Common and high (102 - 104 °F); lasts 3 - 4 days |

Headache | None or mild | Almost always present |

General aches and pains | Mild, if they occur at all | Often severe |

Fatigue, exhaustion, and weakness | Mild, it they occur at all | Extreme exhaustion is early and severe; can last 2 - 3 weeks |

Stuffy nose | Nearly always | Sometimes |

Sneezing | Very common | Sometimes |

Sore throat | Common | Sometimes |

Chest discomfort and cough | Mild-to-moderate, hacking cough | Common, can be severe |

Source: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease | ||

Diagnosing the Flu

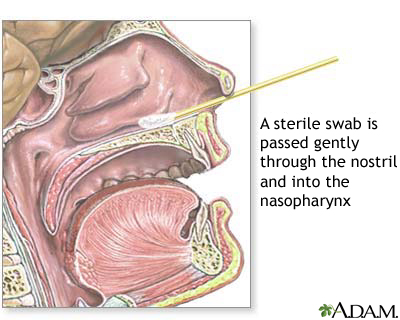

Several available tests can isolate and identify the viruses responsible for some respiratory infections. They are generally not needed, since most cases of the flu are self-evident. Decisions about treatment are almost always made based on how sick an individual is, and whether the person is at risk for more severe complications. If a doctor believes a diagnosis would help, samples using a swab should be taken from the nasal passages or throat within 4 days of the first symptoms.

Several rapid tests for the flu can produce results in less than 30 minutes, but vary on the specific strain or strains that they can detect. They are not as accurate as a viral culture, however, in which the virus is reproduced in the laboratory. Culture results can take 3 - 10 days. Blood tests can also document the infection several weeks after symptoms appear.

Diagnosing Avian Influenza

In February 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a faster test for diagnosing H5 strains of avian influenza in people suspected of having the virus. The test is called A/H5N1 Flu Test. The test gives preliminary results within 40minutes. Older tests required 3-4 hours. It checks for the presence of the protein NS1, which indicates an influenza H5N1 strain, the current strain of concern.

Other Causes of Congestion

Ruling out Allergic Rhinitis. Symptoms of allergic rhinitis include nasal obstruction and congestion, which are similar to the symptoms of a cold. People with allergies, however, are likely to have the following:

- Thin, clear, and runny nasal discharge

- An itchy nose, eyes, or throat

- Recurrent sneezing

There are two forms of allergic rhinitis:

- Symptoms that appear only during allergy season are called allergic rhinitis, commonly known as hay or rose fever. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #77: Allergic rhinitis.]

- Allergens in the house, such as house dust mites, molds, and pet dander, can cause year-long allergic rhinitis, referred to as perennial rhinitis.

Ruling out Sinusitis. The signs and symptoms suggestive of true acute sinusitis include the following:

- A return of congestion and discomfort after initial improvement in a cold (called double sickening)

- Purulent (pus-filled) nasal secretion

- A lack of response to decongestant or antihistamine

- Pain in the upper teeth or pain on one side of the head

- Pain above or below both eyes when leaning over

Children with sinusitis are less likely to have facial pain and headache and may only develop a high fever or prolonged upper respiratory symptoms (such as a daytime cough that does not improve for 11 - 14 days). When the diagnosis is unclear or complications are suspected, further tests may be required. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #62: Sinusitis.]

Other Causes of Coughing

Acute Bronchitis. Acute bronchitis is usually caused by a virus and in most cases is self-limiting. The cough it causes typically lasts for about 7 - 10 days, but in about half of patients, coughing can last for up to 3 weeks, and 25% of patients continue to cough for over 1 month.

Atypical Pneumonia. Pneumonia caused by atypical organisms (such as Mycoplasma pneumonia, chlamydia, and Legionella) can cause symptoms similar to the flu. Only laboratory tests can diagnose the difference. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #64: Pneumonia.]

Ruling out other Viral Infections. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and possibly human parainfluenza viruses (HPV), are proving to be important causes of serious respiratory infections in infants, the elderly, and people with damaged immune systems. (Both also cause mild conditions.) RSV may be a much more common cause of flu-like symptoms than previously thought.

Pertussis. Pertussis (whooping cough) was a very common childhood illness throughout the first half of the century. Although immunizations caused a decline in cases to only 1,730 in the U.S. in 1980, the incidence has risen recently, with nearly 17,000 cases in 2009. Many more cases are reported worldwide.

Nearly half of pertussis cases now occur in people 10 years of age or older, perhaps due to waning immunity in adolescents and adults. Up to 25% of adults who see a doctor for persistent cough may actually have pertussis. It may go undiagnosed, however, because their symptoms are usually mild, and adults are unlikely to have the classic "whooping" cough. This is of some concern because such adults may unknowingly infect unvaccinated children. The younger the patient with pertussis, the higher the risk for severe complications, including pneumonia, seizures, and even death. Children younger than 6 months are at particular risk because protection is incomplete, even with vaccination.

Pertussis vaccines safe for older children and adults are now available.

Other Causes of Sore Throat

In addition to common cold viruses, other, less frequent causes of sore throat include the following:

- Strep throat

- Foodborne and waterborne infections (Streptococcus C and G)

- An uncommon organism called Arcanobacterium haemolyticum (infection with this bacterium can mimic strep throat and may even cause a rash)

- Infectious mononucleosis ("mono")

- Herpesvirus 1

What is Strep Throat?

Group A Streptococcal bacteria is the most common bacterial cause of the severe sore throat known commonly as "strep throat." It occurs mostly in school age children, but people of all ages are susceptible. (Strep throat constitutes about 12% of all sore throat cases seen by doctors.)

The symptoms of strep throat include the following:

- A sudden onset of severe sore throat

- Difficulty in swallowing

- Fever

- Headache

- Stomach pain

- Vomiting

Only about half of patients with strep throat have such clear-cut symptoms. Furthermore, half of people who have these symptoms do not actually have strep throat.

How Is Strep Throat Diagnosed? Most cold-related sore throats are caused by viruses and require no treatment. They usually do not last more than a day. When the sore throat persists and is very painful the doctor will want to rule out or confirm the presence of the Streptococcus bacteria.

- The doctor will look for redness and pus-filled patches on the tonsils and back of the throat.

- The doctor will feel the sides of the neck for swollen lymph nodes. If the lymph nodes are not swollen, it is less likely to be a strep throat.

- A cotton swab is used to take a sample of pus in the throat for a throat culture.

A throat culture is the most effective and least expensive test for confirming the presence of strep throat. It takes 24 - 48 hours to obtain a result.

Rapid Antigen-Detection Test for Strep Throat. A faster test, called the Rapid Strep Antigen Test, uses chemicals to detect the presence of bacteria in a few minutes. A positive result nearly always means that streptococcal bacteria are present in the throat. The test, however, fails to detect 5 - 10% of cases, so a culture may still be necessary to catch any missed infections, particularly in children.

How Serious is Strep Throat? The use of antibiotics has removed the threat of most complications from streptococcus infection in the throat. However, untreated strep throat could lead to the following complications:

- Abscess in the tonsils

- Scarlet fever

- Rheumatic fever (rare in the U.S.)

Complications

Colds rarely cause serious complications. In about 1% of cases, a cold can lead to other complications, such as sinus or ear infections. It can also aggravate asthma and, in uncommon situations, increase the risk for lower respiratory tract infections.

Ear Infections. The rhinovirus, a major cause of colds, also commonly predisposes children to ear infections, possibly by blocking the Eustachian tube, which leads to the middle ear. Viruses may even attack the ear directly.

Sinusitis. Between 0.5 - 3% of people with colds develop sinusitis, an infection in the sinus cavities (air-filled spaces in the skull). Sinusitis is usually mild, but if it becomes severe, antibiotics generally eliminate further problems.

Lower Respiratory Tract Infections. The common cold poses a risk for bronchitis and pneumonia in nursing home patients, and in other people who may be vulnerable to infection.

Aggravation of Asthma. Rhinovirus infections can aggravate asthma in both children and adults. In fact, rhinovirus has been reported to be the most common infectious organism associated with asthma attacks. Problems with wheezing may persist for weeks after a cold.

Complications of Influenza

The flu is usually self-limited. However, each flu season is unpredictable and can make varying numbers of people dangerously sick. According to the CDC, between 1976 and 2006, flu-associated deaths ranged from about 3,000 to 49,000. People at highest risk for serious complications from seasonal flu are those over 65 years old and those with chronic medical conditions. Influenza A is the most severe strain. Influenza B tends to be milder.

Unlike the seasonal flu, children younger than 5 years old, especially those younger than age 2, with H1N1 (swine) flu are also at risk for more serious complications. Pregnant women with H1N1 influenza are also at increased risk for complications.

Pneumonia. Pneumonia is the major serious complication of influenza and can be very serious. It can develop about 5 days after the flu. More than 90% of the deaths caused by influenza and pneumonia occur among older adults.

Flu-related pneumonia nearly always occurs in high-risk individuals. It should be noted that pneumonia is an uncommon outcome of influenza in healthy adults.

Complications in the Central Nervous System in Children. Influenza increases the risk for complications in the central nervous system of small children. Febrile seizures are the most common neurologic complication in children. The risks decline after a child turns 1 year old, but are still high in children aged 3 - 5 years old.

Risk Factors

Age

The very young and the very old are at higher risk for upper respiratory tract infections and their associated complications.

Children. Young children are prone to colds and may have as many as 12 colds every year. Millions of cases of influenza develop in American children and adolescents each year.

Before the immune system matures, all infants are susceptible to upper respiratory infections, with a possible frequency of one cold every 1 - 2 months. Smaller nasal and sinus passages also make younger children more vulnerable to colds than older children and adults. Upper respiratory infections gradually diminish as children grow, until at school age their rate of such infections is about the same as an adult's. There is almost never cause for concern when a child has frequent colds, unless the colds become unusually severe or more frequent than usual.

The Elderly. The elderly have diminished cough and gag reflexes, and their immune systems are often weaker. They are therefore at greater risk for serious respiratory infections than the young and middle-aged adults.

Exposure to Smoke and Environmental Pollutants

The risk of respiratory infections is increased by exposure to cigarette smoke, which can injure airways and damage the cilia (tiny hair-like structures that help keep the airways clear). Toxic fumes, industrial smoke, and other air pollutants are also risk factors. Parental smoking increases the risk of respiratory infections in their children.

Medical Conditions

People with AIDS and other medical conditions that damage the immune system are extremely susceptible to serious infections.

Cancers, especially leukemia and Hodgkin's disease, put patients at risk. Patients who are on corticosteroid (steroid) treatments, chemotherapy, or other medications that suppress the immune system are also prone to infection.

People with diabetes are at a higher risk for the flu.

Certain genetic disorders predispose people to respiratory infections. They include sickle-cell disease, cystic fibrosis, and Kartagener syndrome (which results in malfunctioning cilia).

People under Stress

A number of studies suggest that stress increases one's susceptibility to a cold. Stress appears to increase the risk for a cold regardless of lifestyle or other health habits. And once a person catches a cold or flu, stress can make symptoms worse.

It is not clear why these events occur. Some experts believe that stress alters specific immune factors, which cause inflammation in the airways.

Seasonal Incidence

Colds and the flu occur predominantly in the winter. Flu season typically starts in October and lasts into mid March.

The reasons for this seasonal bias are not due to the cold itself, but to other factors. Certainly, the flu and colds are more likely to be transmitted in winter because people spend more time indoors and are exposed to higher concentrations of airborne viruses. Dry winter weather also dries up nasal passages, making them more susceptible to viruses. Some experts theorize that the high rates of viral infections in winter may be due to certain immune factors, which react to light and dark and affect a person's susceptibility to viruses.

Traveling in Trains, Buses, and Planes

Traveling in close contact with people, whether on trains, planes, or buses, can increase the risk for respiratory infections.

Day Care Centers

Children who attend day care may have an increased risk of colds. However, they may have lower cold rates in their first years of regular school. The colds they catch in day care, then, may bestow some immunity to future colds for a few years. By age 13, such protection has worn off. There is also some evidence that frequent colds in young children may help protect against future allergies and asthma.

Prevention

Because colds and the flu are easily spread, everyone should always wash their hands before eating and after going outside. Ordinary soap is sufficient. Waterless hand cleaners that contain an alcohol-based gel are also effective for everyday use and may even kill cold viruses.

Antibacterial Products

Antibacterial soaps add little protection, particularly against viruses. In fact, one study suggests that common liquid dish washing soaps are up to 100 times more effective than antibacterial soaps in killing respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which is known to cause pneumonia. Wiping surfaces with a solution that contains one part bleach to 10 parts water is very effective in killing viruses. Alcohol-based hand cleaners are very effective, as mentioned above, and are recommended by the CDC.

Temperature

Colds are not caused by insufficiently warm clothes or by going outside with wet hair.

Treatment

The following are some food and fluid recommendations. Most will not cure a cold, but they may help a person deal better with the symptoms:

- Drinking plenty of fluids and getting lots of rest when needed is still the best bit of advice to ease the discomforts of the common cold. Water is the best fluid and helps lubricate the mucous membranes. (There is no evidence that drinking milk will increase or worsen mucus.)

- Chicken soup does indeed help congestion and body aches. The hot steam from the soup may be its chief advantage, although laboratory studies have actually reported that ingredients in the soup may have anti-inflammatory effects. In fact, any hot beverage may have similar soothing effects from steam. Ginger tea, fruit juice, and hot tea with honey and lemon may all be helpful.

- Spicy foods that contain hot peppers or horseradish may help clear sinuses.

Vitamins

Despite a few studies that suggest that large doses of vitamin C may reduce the duration of a cold, most of the scientific evidence finds no benefit. Taking high doses of vitamin C is not recommended, for the following reasons:

- High doses of vitamin C may cause headaches, intestinal and urinary problems, and even kidney stones.

- Because vitamin C increases iron absorption, people with certain blood disorders, such as hemochromatosis, thalassemia, or sideroblastic anemia, should avoid high doses of this vitamin.

- Large doses of vitamin C can also interfere with anticoagulant medications ("blood thinners"), blood tests used in diabetes, and stool tests.

In addition, a review of evidence suggests that taking large doses of vitamin C after the onset of cold symptoms does not improve the symptoms or shortens the duration of the cold.

Zinc

Zinc appears to influence the immune system and it may have a direct effect on viruses. Zinc preparations in lozenge or nasal gel form are marketed as cold treatments. Studies are very mixed on the effects of zinc on colds. A review of available studies comparing zinc treatment to placebo ("sugar pill") found only one high-quality study, which showed that zinc nasal gels might provide a benefit. The overall benefit of zinc in the prevention of colds remains very doubtful. In any case, no one with an adequate diet and a healthy immune system should take zinc for prolonged periods, for the purpose of preventing colds.

Side Effects. Side effects, particularly of the lozenges form, include the following:

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Bad taste (possibly only with zinc gluconate lozenges)

- Severe vomiting, dehydration, and restlessness (signs of overdose, seek medical help)

- Allergic response (rare)

In 2009, the FDA issued a warning regarding Zicam nasal gel swabs containing zinc. The FDA has received reports of cases of anosmia (loss of the sense of smell) following use of these products. These reports are corroborated by several studies connecting nasal zinc applications with anosmia. The reports concerned only nasal gel containing zinc, not oral preparations of zinc.

Food and Drug Interactions. Zinc may also interact with drugs or other elements:

- It may reduce absorption of certain antibiotics.

- Foods high in calcium or phosphorus may reduce zinc absorption.

- In high doses and for long periods of time, zinc can cause copper deficiencies.

Medications for Mild Pain and Fever Reduction

Many people take medications to reduce mild pain and fever. Adults most often choose aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil), or acetaminophen (Tylenol).

The following are recommendations for children:

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (usually Advil or Motrin) are the typical pain-relievers parents give their children. Most pediatricians advise such medications for children who run fevers over 101 °F. Some suggest alternating the two agents, although there is no evidence that this regimen offers any benefits, and it might be harmful.

- Aspirin and aspirin-containing products should never be used in children or adolescents. Reye syndrome, a very serious condition that can be life threatening, has been associated with aspirin use in children who have flu symptoms or chicken pox.

Nasal Strips

Nasal strips (such as Breathe Right) are placed across the lower part of the nose and pull the nostrils open. These strips may open the nasal passages and claim to ease congestion due to a cold, sinusitis, or hay fever. As of yet, there is no scientific evidence that they offer such benefits.

Nasal Wash

A nasal wash can be helpful for removing mucus from the nose. A saline solution can be purchased at a drug store or made at home. If you make a salt solution at home, you should first boil tap water and carefully clean and dry any device that was used to store the water. Although nasal washes have long been recommended, one study reported that neither a homemade solution (using one teaspoon of salt and one pinch of baking soda in a pint of warm water) nor a commercial hypertonic saline nasal wash had any effect on symptoms. Further, one preliminary study found that over-the-counter saline nasal sprays that contain benzalkonium chloride as a preservative may actually worsen symptoms and infection.

Some physicians, however, advocate a traditional nasal wash that has been used for centuries and is different from that used in most studies. It contains no baking soda and uses more fluid for each dose and less salt. The nasal wash should be performed several times a day.

A simple method for administering a nasal wash:

- Lean over the sink head down.

- Pour some solution into the palm of the hand and inhale it through the nose, one nostril at a time.

- Spit the remaining solution out.

- Gently blow the nose.

The solution may also be inserted into the nose using a large rubber ear syringe, available at a pharmacy. In this case, the process is the following:

- Lean over the sink head down.

- Insert only the tip of the syringe into one nostril.

- Gently squeeze the bulb several times to wash the nasal passage.

- Then press the bulb firmly enough so that the solution passes into the mouth.

- The process should be repeated in the other nostril.

Nasal-Delivery Decongestants

Nasal-delivery decongestants are applied directly into the nasal passages with a spray, gel, drops, or vapors. Nasal forms work faster than oral decongestants and have fewer side effects. They often require frequent administration, although long-acting forms are now available. Ingredients and brands of nasal decongestants include the following:

Long Acting Nasal-Delivery Decongestants. They are effective in a few minutes and remain so for 6 - 12 hours. The primary ingredient in long-acting decongestant is:

- Oxymetazoline: Brands include Vicks Sinex (12-hour brands), Afrin (12-hour brands), Dristan 12-Hour, Good Sense, Nostrilla, Neo-Synephrine 12-Hour

- Xylometazoline: Inspire, Otrivin, Natru-vent

Short-Acting Nasal-Delivery Decongestants. The effects usually last about 4 hours. The primary ingredients in short-acting decongestants are:

- Phenylephrine: Neo-Synephrine (mild, regular, high-potency), 4-Way, Dristan Mist Spray, Vicks Sinex

- Naphazoline (Naphcon Forte, Privine)

Dependency and Rebound. The major hazard with nasal-delivery decongestants, particularly long-acting forms, is a cycle of dependency and rebound effects. The 12-hour brands pose a particular risk for this effect. This effect works in the following way:

- With prolonged use (more than 3 - 5 days), nasal decongestants lose effectiveness and even cause swelling in the nasal passages.

- The patient then increases the frequency of their dose. The congestion worsens, and the patient responds with even more frequent doses, in some cases as often as every hour.

- Individuals then become dependent on them.

Tips for Use. The following precautions are important for people taking nasal decongestants:

- When using a nasal spray, spray each nostril once. Wait a minute to allow absorption into the mucosal tissues, and then spray again.

- Keep the nasal passages moist. All forms of nasal decongestants can cause irritation and stinging. They also may dry out the affected areas and damage tissues.

- Do not share droppers and inhalators with other people.

- Use decongestants only for conditions requiring short-term use, such as before air travel or for a single-allergy attack. Do not take them more than 3 days in a row. With prolonged use, nasal decongestants become ineffective and result in the so-called rebound effect and dependence.

- Discard sprayers, inhalators, or other decongestant delivery devices when the medication is no longer needed. Over time, these devices can become reservoirs for bacteria.

- Discard the medicine if it becomes cloudy or unclear.

Oral Decongestants

Oral decongestants also come in many brands, which mainly differ in their ingredients. The most common active ingredient are pseudoephedrine (Sudafed, Actifed, Drixoral) or phenylephrine (Sudafed PE and many other cold products). (Note that pseudoephdrine sales are restricted in many communities because of potential use in the manufacturing of meth.)

Side Effects of Decongestants. Decongestants have certain adverse effects, which are more apt to occur in oral than nasal decongestants and include the following:

- Agitation and nervousness

- Drowsiness (particularly with oral decongestants and in combination with alcohol)

- Changes in heart rate and blood pressure

Avoid combinations of oral decongestants with alcohol or certain drugs, including monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) and sedatives.

Individuals at Risk for Complications from Decongestants. People who may be at higher risk for complications are those with certain medical conditions, including disorders that make blood vessels highly susceptible to contraction. Such conditions include the following:

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Thyroid disease

- Diabetes

- Prostate problems that cause urinary difficulties

- Migraines

- Raynaud's phenomenon

- High sensitivity to cold

- Emphysema or chronic bronchitis

Anyone with the above conditions should not use either oral or nasal decongestants without a doctor's guidance. In addition, people taking medications that increase serotonin levels, such as certain antidepressants, anti-migraine agents, diet pills, St. John's wort, and methamphetamine, should avoid decongestants. The combinations can cause blood vessels in the brain to narrow suddenly, causing severe headaches and even stroke.

Others who should use these drugs with caution are the following (consult your health care provider):

- Anyone who is pregnant.

- Children: Children appear to metabolize decongestants differently than adults. Decongestants should not be used at all in infants and small children under the age of 4. Young children are at particular risk for side effects that depress the central nervous system. Such symptoms cause changes in blood pressure, drowsiness, deep sleep, and, rarely, coma. Studies have also shown that these cough and cold products generally are not effective in the treatment of children under 6 years of age.

In October 2007, drug manufacturers voluntarily withdrew from the market all oral cough and cold products, including decongestants, aimed at children under 2, due to potential harm from misuse. In late 2008, the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, which represents most of the US makers of nonprescription over-the-counter cough and cold medicines in children, began voluntarily modifying its products' labels to read "Do Not Use in Children Under 4." This action is supported by the FDA.

Under no circumstances should children be given adult medicines, including over-the-counter medications.

Cough Remedies

Major studies have indicated that over-the-counter cough medicines are not very effective, but they are also not harmful.

- For thick phlegm, patients may try cough medications that contain guaifenesin (Robitussin, Scot-Tussin Expectorant), which loosens mucus. Patients should not suppress coughs that produce mucus and phlegm. It is important to expel this substance. To loosen phlegm, patients should drink plenty of fluids and use a humidifier or steamer.

- For patients with a dry cough, a suppressant may be useful, such as one that contains dextromethorphan (Drixoral Cough, Robitussin Maximum Strength Cough Suppressant).

Medications that contain both a cough suppressant and an expectorant are not useful and should be avoided. Medicated cough drops that contain dextromethorphan are not very useful. A patient is just as likely to find relief from hard candy or lozenges.

Prescription cough medications with small doses of narcotics are available. They are usually reserved for lower respiratory infections with significant coughs.

Remedies for Sore Throat Associated with Colds

Sore throats that are associated with colds are generally mild. The following may be helpful:

- Cough drops, throat sprays, or gargling warm salt water may help relieve sore throat and reduce coughing.

- Throat sprays that contain phenol (such as Vicks Chloraseptic) may be helpful for some.

- Cough drops that contain menthol and mild anesthetics, such as benzocaine, hexylresorcinol, phenol, and dyclonine (the most potent), may soothe a mild sore throat.

- People with sore throats from postnasal drip might try taking a teaspoon of liquid antacid. They shouldn't drink anything afterward, since the intention is to coat the throat and help neutralize the acid in the mucus that might be causing pain.

If soreness in the throat is very severe and does not respond to mild treatments, the patient or parent should check with the physician to see if a strep throat is present, which would require antibiotics. [See "What is Strep Throat?" in the Diagnosis section of this report.]

Combination Cold and Flu Remedies and Antihistamines

Dozens of remedies are available that combine ingredients aimed at more than one cold or flu symptom. In general, they do no harm, but they have the following problems:

- Some ingredients may produce side effects without even helping a cold.

- In some cases, the ingredients conflict (such as a cough expectorant and a cough suppressant).

- In other cases, a patient may wish to increase the dosage to improve one symptom, which serves to increase other ingredients that do no good and, in higher doses, may cause side effects.

Acetaminophen. Many cold and flu remedies contain acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol. Acetaminophen in high dosages can cause serious liver injury. When taking combination medicines, always check the ingredients for the presence of acetaminophen, and be sure never to take more than the recommended daily dose of 4g acetaminophen.

Note on Antihistamines. Many combination remedies contain antihistamines. Antihistamines are used principally for allergies and the common cold. First-generation antihistamines may reduce cold symptoms by drying out nasal passages; this may help with a running nose caused by colds (but it also interferes with treatments of sinusitis). Their benefits for the cold are likely to be due to the drowsiness they cause. Such antihistamines include Benadryl, Tavist, and Chlor-Trimeton. The newer, second-generation antihistamines (Claritin, Allegra, Zyrtec) do not have these effects and also appear to have no benefits against colds.

Herbs and Supplements

Herbal remedies and dietary supplements are not regulated by the FDA. This means that manufacturers and distributors do not need FDA approval to sell their products. However, any substance that affects the body's chemistry can, like any drug, produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been numerous reported cases of serious and even deadly side effects from herbal products.

The following are special concerns for people taking natural remedies for colds or influenza:

- Echinacea is commonly taken to prevent onset and ease symptoms of colds or flu. High quality studies have failed to show that this herb helps prevent or treat colds. In addition, some people are allergic to echinacea. People who have autoimmune diseases or plant allergies should avoid it. There have been a few reports of people experiencing a skin reaction to this herb. This particular reaction, called erythema nodosum, which is characterized by tender, red nodules under the skin.

- Chinese herbal cold and allergy products can contain trace amounts of aristolochic acid, a chemical that causes kidney damage and cancer. Many herbal remedies imported from Asia may contain potent pharmaceuticals, such as phenacetin and steroids, as well as toxic metals.

Medications

Vaccines are available to prevent influenza (See Viral Influenza Vaccines section in this report).

For mild influenza, symptom relief is similar to that for colds.

Who Needs Antiviral Drugs

Two classes of antiviral agents have been developed to treat influenza: neuraminidase inhibitors and M2 inhibitors. These drugs can shorten symptoms but there is no indication that they can prevent or reduce complications such as pneumonia. They do not help if they are started after the first 36 hours of illness. Because of emerging drug resistance, some experts suggest these drugs be reserved for severely ill patients or those at high risk.

Most people who get seasonal or H1N1 flu will likely recover without needing medical care. Doctors, however, can prescribe antiviral drugs to treat people who become very sick with the flu or are at high risk for flu complications.

If you need treatment for the flu, the CDC recommends that your doctor give you zanamivir (Relenza) or osteltamivir (Tamiflu). These drugs work best if you receive them within 2 days of becoming ill. You may get them later if you are very sick or if you have a high risk for complications.

Those at high risk for complications and are more likely to need treatment include:

- People with weakened immune systems, such as AIDS patients or patients being treated for cancer

- Elderly patients, particularly patients in nursing home

- Very young children (it may be difficult to tell whether pneumonia is related to influenza or caused by respiratory syncytial virus [RSV])

- Hospitalized patients and anyone with serious medical conditions, such as diabetes, heart, circulation, or lung disorders, particularly chronic lung disease

- Drug abusers who use needles

- Pregnant woman, especially those suspected of having H1N1 flu

To prevent infection with H1N1 flu, people living in the same house as someone diagnosed with the virus who also are risk for complications should ask their doctor if they also need a prescription for these medicines.

Anti-Viral Drugs: Neuraminidase Inhibitors

Brands and Benefits. Zanamivir (Relenza) and oseltamivir (Tamiflu) are neuraminidase inhibitors. They are newer agents that have been designed to block a key viral enzyme, neuraminidase, which is involved with viral replication. While effective, their overall benefit is modest.

Important points about the use of these drugs:

- The main benefit of these drugs is a reduction in the length of symptoms by about one day, and only when started within 48 hours after symptoms become evident. They may be used for treating both A and B strains of influenza.

- They may help reduce transmission of the virus.

- Both show some benefits for preventing influenza. Only oseltamivir has been approved for this purpose, however, and only in people over 13.

- They may reduce complications of influenza, although this needs to be confirmed. It is not yet known if they have any effect on overall survival rates.

- Oseltamivir is the only drug studied in avian flu cases. Although it is active in lab experiments, it has not been successful clinically. Experience is very limited, however, and it is not clear whether people infected with avian flu received the drug in time for it to be useful.

Limitations and Side Effects. Although they have many advantages compared to the M2 inhibitors, neuraminidase inhibitors are much more expensive. They also need to be taken within 2 days of the start of symptoms to be effective. Neither neuraminidase inhibitor is effective against influenza-like illness (one that is not caused by an influenza virus). There are also some differences between the two drugs that could be significant for some individuals:

- Zanamivir is administered through an inhaler. People with asthma or other lung disorders may experience airway spasms and should use this drug with caution. Side effects are generally minor in most patients. It is important to make sure that elderly patients are able to properly use the zanamivir inhaler device. Zanamivir should ONLY be used in its original inhaler device.

- Oseltamivir comes in capsule and liquid form. Side effects are also minor, but about 10 - 15% of patients experience nausea and vomiting. Patients with kidney dysfunction should take lower doses.

The current use of neuraminidase inhibitors in different age and patient groups is as follows:

- Adults: Both drugs are approved for treatment in adult patients.

- Children: Oseltamivir is approved for use in children age one and older. Studies report significant reduction in symptoms and in the incidence of ear infections in this population. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends the following: Therapy should be provided to children with influenza infection who are at high risk of severe infection, and to children with moderate-to-severe influenza infection who may benefit from a decrease in the duration of symptoms. Prophylaxis should be provided (1) to high-risk children who have not yet received immunization and during the 2 weeks after immunization, (2) to unimmunized family members and health care professionals with close contact with high-risk unimmunized children or infants who are younger than 6 months, and (3) for control of influenza outbreaks in unimmunized staff and children in an institutional setting.

- High-risk Patients. Recent studies indicate neuraminidase inhibitors are safe and effective in patients with serious medical problems or other conditions that put them at risk for complications of flu.

A third neuroaminidase product, peramivir, is now in clinical trials. However, it was authorized as emergency treatment for severely ill, hospitalized patients with H1N1 "swine" flu. This authorization was terminated in June 2010. Peramivir is given intravenously.

Anti-Viral Drugs: M2 Inhibitors

Brands and Benefits. Amantadine (Symmetrel) and rimantadine (Flumadine) are M2 inhibitors. The following benefits may apply to the minority of strains of influenza A that remain sensitive to the drugs:

- Both offer some protection against influenza A and prevent severe illness if a person contracts the infection. (To be effective, it must be administered within 2 days of onset.)

- They may shorten the duration and lessen the severity of the flu if given within 48 hours of onset of symptoms.

Limitations. Drawbacks of M2 inhibitors include:

- They are not effective against the 2011-2012 flu strains.

- Viral resistance to these agents is rapidly increasing.

- M2 inhibitors are not effective against influenza B.

- Neither drug has proven to reduce the risk for complications of the flu, including pneumonia and bronchitis.

Side Effects. Both M2 inhibitors occasionally cause nausea, vomiting, indigestion, insomnia, and hallucinations. Amantadine affects the nervous system and about 10% of people experience nervousness, depression, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, and lightheadedness. Rimantadine is less likely to do so. Rarely, amantadine can cause seizures.

Note: Amantadine is a standard treatment for Parkinson's disease and should be continued for that condition.

Influenza Vaccines

"Flu Shots." These vaccines use inactivated (not live) viruses. They are designed to provoke the immune system to attack antigens found on the surface of the virus. (Antigens are foreign molecules that the immune system specifically recognizes as alien and targets for attack.)

Unfortunately, the antigens in these influenza viruses undergo genetic changes (called antigenic drift) over time, so they are likely to become resistant to a vaccine that worked in the previous year. Vaccines are then redesigned annually to match the current strain.

- Influenza A. The influenza A virus is further categorized by primary molecular antigens (hemagglutinin and neuraminidase), which serve as the targets for the vaccines. Influenza A is a particular problem, because it can infect other species, such as pigs or chicken, and undergo major genetic changes.

- Influenza B viruses tend to be more stable than influenza A viruses, but they too vary. Although influenza B has been far less common than A, a vaccine for type B is important because experts are concerned that small children will not have developed any immunity to the virus, and will experience severe flu if they are exposed to type B viruses.

Injectable vaccines. There are 3 types of influenza injectable vaccines:

- The regular killed vaccine is licensed for use in everyone 6 months and older.

- The intradermal injection uses a much smaller needle, and a smaller dose of the same killed vaccine. It is injected into the skin instead of the muscle.

- The high-dose injection is for people 65 and older, whose immune system is possibly weaker as a result of normal aging. This killed vaccine is identical to the other two in the strains it carries, but delivers a much higher dose of the antigens, to create a strong immune response in the recipients.

Intranasal (inside the nose) vaccine. A live but weakened intranasal vaccine (FluMist) is proving to be effective and safe in healthy, non-pregnant people aged 2 - 49 years and has been approved by the FDA. It is known as a live, attenuated, intranasal influenza vaccine (LAIV). The vaccine is engineered to grow only in the cooler temperatures of the nasal passages, not in the warmer lungs and lower airways. It boosts the specific immune factors in the mucous membranes of the nose that fight off the actual viral infections. FluMist is given using a nasal spray. It should NOT be used in those who have asthma or in children under age 5 who have repeated wheezing episodes.

Timing and Effectiveness of the Vaccine. Ideally, everyone should be vaccinated every October or November. However, it may take longer for a full supply of the vaccine to reach certain locations. In such cases, the high-risk groups should be served first.

Antibodies to the flu virus usually develop within 2 weeks of vaccination, and immunity peaks within 4 - 6 weeks, then gradually wanes.

- Children younger than 9 years of age, who have not been previously vaccinated or received only 1 dose the previous year should be given 2 vaccine doses, spaced 4 weeks apart.

- It should be noted that if an individual develops flu symptoms and is accurately diagnosed in time, vaccination of the other members of the household within 36 - 48 hours affords effective protection to those individuals, according to a 2004 Canadian analysis of multiple studies.

In healthy adults, immunization typically reduces the chance of getting the seasonal flu by about 70 - 90%. The current flu vaccines may be slightly less effective in certain patients, such as the elderly and those with certain chronic diseases. Some evidence suggests, however, that even in people with a weaker response, the vaccine is usually protective against serious flu complications, particularly pneumonia. Some evidence suggests that among the elderly, a flu shot may help protect against stroke, adverse heart events, and death from all causes.

Everyone aged 6 months and over should get a flu vaccine; the only exception is for those who are allergic to the vaccine. Vaccination is especially important in the following groups, who are at a high risk for complications from the flu:

- People who are 50 or more years of age

- People who are 6 to 49 months of age

- People who have chronic lung disease, including asthma and COPD, or heart disease

- People who are 18 years old or younger AND taking long-term aspirin therapy

- People who have sickle cell anemia or other hemoglobin-related disorders

- People who have kidney disease, anemia, diabetes, or chronic liver disease

- People who have a weakened immune system (including those with cancer or HIV/AIDS)

- People who receive long-term treatment with steroids for any condition

- Women who are pregnant or plan to become pregnant during the flu season. Women who are pregnant should receive only the inactivated flu vaccine. (Vaccinations should usually be given after the first trimester. Exceptions may be women who are in their first trimester during flu season, because their risk from complications of the flu is higher than any theoretical risk to the baby from the vaccine)

Negative Effects

Possible side effects of the flu vaccine include:

- Allergic Reaction. Newer vaccines contain very little egg protein, but an allergic reaction still may occur in people with strong allergies to eggs.

- Soreness at the Injection Site. Up to two-thirds of people who receive the influenza vaccine develop redness or soreness at the injection site for 1 or 2 days afterward.

- Flu-like Symptoms. Some people actually experience flu-like symptoms, called oculorespiratory syndrome, which include conjunctivitis, cough, wheeze, tightness in the chest, sore throat, or a combination. Such symptoms tend to occur 2 - 24 hours after the vaccination and generally last for up to 2 days. It should be noted that these symptoms are not the flu itself but an immune response to the virus proteins in the vaccine. (Anyone with a fever at the time the vaccination is scheduled, however, should wait to be immunized until the ailment has subsided.)

- Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Isolated cases of a paralytic illness known as Guillain-Barre syndrome have occurred, but if there is any higher risk following the flu vaccine, it is very small (one additional case per 1 million people), and does not outweigh the benefits of the vaccine. Guillain-Barre syndrome resolves in most cases, but recovery is slow.

There has been some question concerning influenza vaccinations because of reports that these vaccines may worsen asthma. Recent and major studies have been reporting, however, that the vaccination is safe for children with asthma. It is also very important for these patients to reduce their risk for respiratory diseases.

Avian Influenza Vaccine

The FDA approved the first vaccine for humans against H5NI influenza virus in April 2007. The vaccine, which is made from a human strain of the virus, could be used in people ages 18 - 64 to prevent the spread of the virus from human to human. The vaccine requires two doses, given about a month apart. It will not be sold commercially, but instead is being purchased by the U.S. government to be stockpiled and distributed to public health officials in the event of an outbreak of avian flu. The vaccine led to the development of antibodies in 45% of those who received the higher dose studied. The most common side effects reported were pain at the injection site, headache, and muscle pain. Research on the vaccine is continuing.

A new vaccine, currently in clinical trials, is made from artificial virus-like particles -- a collection of proteins that look like the outside of the virus but are made in the lab and cannot reproduce.

Who Needs Antibiotic

How Is Strep Throat Treated? Strep throat infections require antibiotics. Antibiotics prevent a serious complication called rheumatic fever, which can result in permanent damage to the heart. Fortunately, this complication rarely occurs in United States anymore. Antibiotic treatment of strep throat will almost always prevent this complication. In addition, antibiotics shorten the recovery time from strep throat.

The following antibiotics are generally used to treat strep throat:

- Penicillin is usually the antibiotic of choice unless the patient is allergic to it. A full 10 days of treatment may be necessary to clear the infection. Amoxicillin, a form of penicillin, is proving to be effective when taken in a single daily dose for 10 days.

- Macrolide antibiotics. Erythromycin is known as a macrolide antibiotic and is an appropriate choice for patients with penicillin allergies. A 10-day regimen is needed to clear the infection. The drug often causes gastrointestinal distress. Another macrolide, azithromycin, can be given as a single daily dose and is effective in 5 days. It has fewer side effects than erythromycin but is more expensive. Bacterial resistance to macrolides is increasing.

- Cephalosporins are also very effective in eradicating the bacteria. but they may cause reactions in people with severe penicillin allergies.

Antibiotics are very often inappropriately prescribed for non-strep sore throats. Studies indicate that fewer than half of adults and far fewer of the children with even strong signs and symptoms for strep throat actually have strep infections.

Parents should be comforted that a delay in antibiotic treatment while waiting for lab results does not increase the risk that the child will develop serious long-term complications, including acute rheumatic fever. If a patient is severely ill, however, it is reasonable to begin administering antibiotics before the results are back. If the culture is negative (there is no evidence of bacteria), the doctor should call the family to make certain the patient stops taking the antibiotics and any remaining pills are discarded.

Children who have a sore throat and who have had rheumatic fever in the past should receive antibiotics immediately, even before culture results are back. Children with a sore throat who have a family member with strep throat or rheumatic fever should also receive immediate antibiotic treatment.

Antibiotic Resistance

The intense and widespread use of antibiotics is leading to a serious global problem of antibiotic resistance. The inappropriate use of powerful newer antibiotics for conditions such as colds or sore throats poses a particular risk for the development of resistant strains of bacteria. For example, the number of cases of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is increasing in people who have no known risk factors. (MRSA can cause severe skin infections.) In 2006, rates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistance to the fluoroquinolone antibiotics family exceeded 10%. The CDC no longer recommends treating gonorrhea infections with fluoroquinolone first.

When Antibiotics Are Needed for Upper Respiratory Infections.

Antibiotics do not affect viruses and, in healthy individuals, these drugs are not necessary or helpful for influenza or colds, even with persistent cough and thick, green mucus. In one disturbing study, antibiotics were prescribed for nearly half of children who went to the doctor for a common cold.

Antibiotics may be required for upper respiratory tract infections only under certain situations, such as the following:

- Patients, particularly small children or elderly people, who have medical conditions that put them at high risk for complications from any respiratory tract infections, may sometimes be given antibiotics.

- Patients with severe sinusitis that does not clear up within 7 days (some experts say 10 days) and whose symptoms include one or more of the following: green and thick nasal discharge, facial pain, or tooth pain or tenderness. [For more information, see In-Depth Report # 62: Sinusitis.]

- Some children with middle ear infections, although experts differ on who will benefit. Some experts recommend that only children under the age of 2 years should be treated with antibiotics, and children over 2 should be treated on a case-by-case basis. [For more information, see In-Depth Report # 78: Ear Infections.]

- Patients with strep throat or severe sore throat that involves fever, swollen lymph nodes, and absence of cough. (Strep throat makes up only 10 - 15% of all sore throat cases.)

Patients at Highest Risk for Infection with Resistant Bacteria Strains. Some patients are at greater risk for developing an infection resistant to common antibiotics. At this time, the average person is not endangered by this problem. Risk factors include:

- Very old or very young age

- Exposure to patients with drug-resistant infection

- Hospitalization in intensive care units

- History of an invasive surgical procedure

- Staying in the hospital

- Prolonged course of antibiotics, particularly within the past 4 - 6 weeks

- Serious wounds

- Tubes down the throat, catheters, or intravenous (I.V.) lines

- Immunosuppression

Children at higher risk for antibiotic resistance are those who attend day care, who are exposed to cigarette smoke, who were bottle-fed, and who had siblings with recurrent ear infections.

What the Health Care Community Is Doing. Prescribing antibiotics only when necessary is the most important step in restoring bacterial strains that are susceptible to antibiotics. Encouraging studies are reporting that inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions are on the decline. Prescriptions for other common respiratory infections, such as otitis media, sore throat, acute bronchitis, and colds and flus have been decreasing.

What Patients and Parents Can Do. Patients and parents can also help with the following tips:

- Use home or over-the-counter remedies to relieve symptoms of mild upper respiratory tract infections.

- Realize that antibiotics will not shorten the course of a viral infection. It is important for patients and parents to understand that although antibiotics may bring a sense of security, they provide no significant benefit for a person with viral infection, and overuse can contribute to the growing problem of resistant bacteria.

- Don't pressure a doctor into prescribing an antibiotic if it is clearly inappropriate. The doctor very often will give in.

- If a child needs an antibiotic, ask the doctor whether it is appropriate to use high-dose short-term antibiotics, which may lower the risk for developing resistant strains.

- If an antibiotic is prescribed, take the full course, even if you feel better before finishing it.

Resources

- www.cdc.gov/flu -- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- www.niaid.nih.gov -- National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/en -- World Health Organization

- www.cdc.gov/vaccines -- National Immunization Program

- www.immunize.org -- Immunization Action Coalition

- www.entnet.org -- American Academy of Otolaryngology -- Head and Neck Surgery

- www.cdc.gov/flu/avian -- Avian Influenza Information

References

Altamimi S, Khalil A, Khalaiwi KA, Milner R, Pusic MV, Al Othman MA. Short versus standard duration antibiotic therapy for acute streptococcal pharyngitis in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD004872.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2011-2012. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):813-25.

Burch J. Prescription of anti-influenza drugs for healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(9):537-545

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR. 2011;60(33):1128-32.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR.2010;59(31);981-992.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Key Facts About Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Available online.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 - 11 Influenza Prevention & Control Recommendations: Vaccination of Specific Populations. Available online.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute Respiratory Disease Associated with Adenovirus Serotype 14 -- Four States, 2006 - 2007. MMWR. 2007;56(45):1181-84.

Chan TV. The patient with sore throat. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:923-943.

D'Cruze H, Arroll B, Kenealy T. Is intranasal zinc effective and safe for the common cold? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prim Health Care. 2009;1(2):134-139.

GlaxoSmithKline. RELENZA prescribing information. December, 2010.

Interagency Task Force on Antimicrobial Resistance. A Public Health Action Plan to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. Page last revised July 19, 2010. Available online.

Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Del Mar C. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b5106.

Khurana S, Wu J, Verma, N, et al.H5N1 Virus-Like Particle Vaccine Elicits Cross-Reactive Neutralizing Antibodies That Preferentially Bind to the Oligomeric Form of Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin in Humans. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:0945-10954.

Shah SA, Sander S, White CM, Rinaldi M, Coleman CI. Evaluation of echinacea for the prevention and treatment of the common cold: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(7):473-80.

Shaikh N, Leonard E, Martin JM. Prevalence of streptococcal pharyngitis and streptococcal carriage in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e557-564.

Thompson MG et al. Updated Estimates of Mortality Associated with Seasonal Influenza through the 2006-2007 Influenza Season. MMWR. 2010; 59(33): 1057-1062.

Turner RB. The common cold. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2009:chap 53.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Clears Rapid Test for Avian Influenza A Virus in Humans. April 7, 2009. Available online.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Nonprescription Drugs and Pediatric Advisory Committee Meeting. Joint Meeting of the Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee and the Pediatric Advisory Committee October 18-19, 2007. Available online.

World Health Organization. Cumulative Number of Confirmed Human Cases of Avian Influenza A/(H5N1) Reported to WHO. December 15, 2011. Available online.

|

Review Date:

2/12/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |